LONDON – In a development that sent shockwaves through the tweed-wearing elite, the British Museum has been thrown into disarray after a recent discovery challenged their very raison d’etre. Apparently, a rogue intern tasked with dusting a particularly dusty corner of the Rosetta Stone exhibit stumbled upon a shocking revelation: the artifacts on display might, gasp, actually belong to the cultures they were “acquired” from.

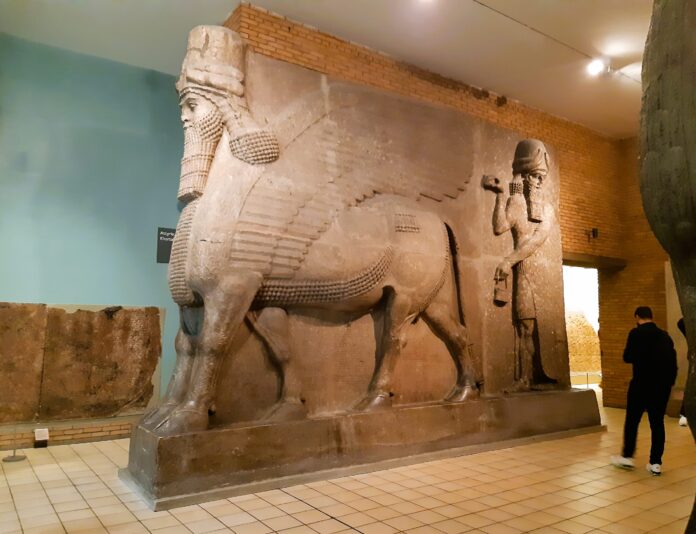

“It’s all quite unsettling,” confided Bartholomew Featherbottom III, a curator with a monocle perpetually perched upon one eye. “Imagine our surprise when young Mildred unearthed a cuneiform tablet explicitly stating the Elgin Marbles were, in fact, not a parting gift from Lord Elgin, but rather… looted from the Parthenon.” This revelation has plunged the museum into existential despair. Decades spent cultivating the image of a benevolent institution showcasing “the march of civilization” have apparently been built on a foundation of, well, plunder.

The British public, ever the picture of stoic indifference, responded with a collective shrug. A recent poll revealed that 72% of respondents were unaware of the museum’s colonial past, while the remaining 28% simply expressed a preference for a decent cup of tea over “foreign squabbles.”

Meanwhile, the international arena is brewing with discontent. Greece, the rightful owner of the aforementioned marbles, has threatened to withhold their annual shipment of halloumi cheese until the situation is rectified. The Egyptian government, ever the comedian, has offered to “loan” the Rosetta Stone back to England – for a “small” fee of £10 billion a year.

The museum itself is scrambling to contain the fallout. A hastily convened committee has brainstormed a variety of “solutions,” each more ridiculous than the last. One proposal involves sending “replica appreciation packages” to the offended nations – think miniature Pyramids made of polystyrene and glow-in-the-dark Tutankhamun masks. Another, even more outlandish, suggests a series of “cultural exchange tours,” where visitors can witness the magnificent emptiness of once-filled galleries.

Of course, there are those who insist on a return to the “good old days” of imperial glory. Lord Percival Fitzwilliam, a particularly pompous trustee, believes this is all a “liberal conspiracy” and that the museum is perfectly within its rights to keep the artifacts. “After all,” he chortled, adjusting his ascot, “who else could possibly curate such a magnificent collection of… borrowed history?”

This ethical quandary raises bigger questions about cultural appropriation and the importance of preserving heritage in its rightful context. But let’s be honest, who has the time for such navel-gazing when there’s a potential halloumi shortage looming?

The future of the British Museum remains uncertain. Will they finally embrace the concept of repatriation, or will they cling desperately to their ill-gotten gains? Only time will tell. In the meantime, perhaps it’s time to explore the rich cultural tapestry of your own local museum (assuming there are still artifacts left on display). Or, for a truly immersive experience, you could visit the British Museum and take a guided tour of their breathtakingly empty galleries. Remember, dear reader, you can’t build an empire on borrowed antiquities – even if they look damn good in a well-lit display case.